I woke up Friday morning to the sad news that former New York Met Matt Harvey was retiring from professional baseball. I’ve spent most of the day getting waves of nostalgia and sadness. A frank reminder about the realities of professional sports and the impact that a life under the spotlight has on those under its brightness.

When Harvey was at his apex, it was incomparable. Those Mets boasted the Madoff Ponzi scheme victim Wilpons crying poor as owners at their most insufferable. Those Mets were 70 win teams littered with fringe major leaguers and the hope of maybe one prospect pitcher blossoming into something special.

Harvey day wasn’t just a baseball game, as a Met fan, it was an event. On 70 win teams, there weren't a whole lot of reasons to tune in. Jordany Valdespin hitting a few grand slams did not exactly have the Flushing faithful glued to SNY or filling the relatively new Citi Field.

No, that was the shooting star Harvey. Gone almost as quickly as he arrived. As a Met, Harvey only pitched 640 innings. That’s all the baseball reference page will say in perpetuity. But, it wasn’t the years, it was the miles. Harvey’s ascent to stardom was a front row ticket to baseball greatness.

From 2012-2015 (Harvey missed the 2014 season with a UCL injury) the Connecticut native had an ERA of 2.53 and struck out 449 batters in 427 innings. He started the All Star Game at Citi Field. Harvey represented the single most important emotion in sports, hope.

As a Met fan, those moments were few and far between. For 61 years of baseball, the Mets have qualified for the postseason ten times. They’ve won the World Series twice. They’ve also had pitchers get hand foot and mouth disease, first basemen suffer from yellow valley fever and a litany of car, horse and other absurd accidents.

But, for that three year window, the Mets featured the best right handed pitcher in baseball. Steven Strasburg, eat your heart out. Harvey was better.

No matter how bleak things were, every fifth day, Harvey would take the mound and the collective buzz was palpable. Jacob deGrom’s last two years as a Met were similar, but those Mets had no expectations. The only thing to look forward to was Harvey taking the ball and hoping the lineup could muster up a single run of support.

As long as I live, I will die on the hill that sending Harvey out for the ninth in game 5 was the right decision. The pitcher earned the right to marshal that game across the finish line with eight of the most delirium inducing innings in the history of the franchise.

If the Mets were gonna bow out in five, they were going out on their shield with their best player firing every last bullet in the gun. Harvey gave the last good baseball of his major league career trying to will the Mets to a game six. If it worked out, these last two paragraphs would be entirely different.

The Life in the spotlight

As Harvey thrived on the field, his natural charisma blossomed off of it. The talkshow circuit, Ranger games, celebrity relationships. There were occasional concerns like him failing to show up for a bullpen during that playoff run, but they were mostly chalked up as immaturity.

The undercurrent of that thread was a very real struggle with addiction that came into focus last year during the trial of Eric Kay, an Anaheim Angels employee. Kay provided the fentanyl laced Oxycodone that Skaggs died from. Kay was sentenced to 22 years in prison this past October for his role in Skaggs death.

During the trial, Kay’s defense team tried to use Harvey’s friendship with Skaggs to sow reasonable doubt that he didn’t provide the fatal oxycodone. Last May, the New York tabloids had a field day digging into Harvey’s mental health struggles and magically sources from the Mets organization manifested to try and clear the team’s name for its role in Harvey’s struggles.

The manager for those mostly mediocre Met teams, Terry Collins, came forward and volunteered that Harvey “talked about killing himself,” during the media circus part of Kay’s trial. The way Harvey’s very real life struggles were used to fill airtime and bylines during the spring last year never sat right with me.

The alleged “whispers and rumors,” that swirled around Harvey during his time in New York only getting reported several years after the fact when the Mets were trying to wash their hands of blame was gross. Flat out. If the Mets really wanted the best for Harvey, they would’ve made better efforts to offer him help.

If Harvey took the help or not is another thing, but the team focusing on running him out there every fifth day didn’t seem to have the player’s best interest in mind.

Professional athletes are conditioned to endure struggle. Their pain tolerance, the ability to gut out significant injury regardless of the long-term impacts is revered and becomes that of myth. The underbelly of that is what teams do to get players ready to gut out those injuries.

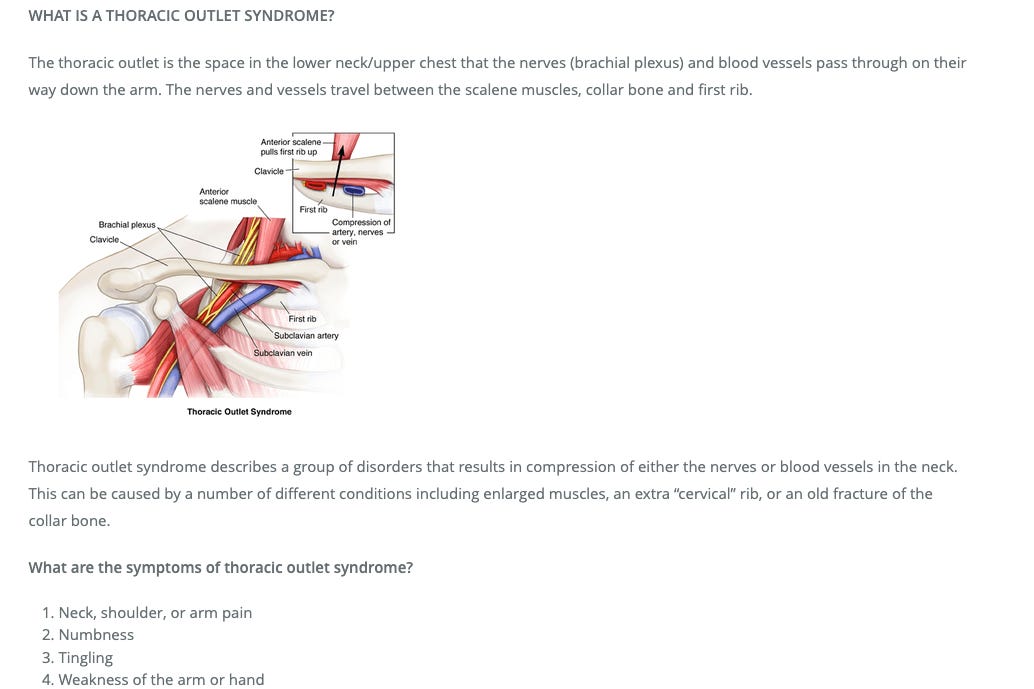

I mentioned Harvey’s UCL injury and the Tommy John surgery that robbed him of the 2014 season but didn’t bring up his 2016 thoracic outlet procedure.

This procedure took away Harvey’s blistering velocity and forced a fundamental reinvention as a pitcher. But, before getting back to the field of play, it’s important to emphasize that’s secondary in this story.

I’m sitting here painfully sad about Harvey’s retirement because of just unfair it all was. A hyper-talented pitcher on a team starved for talent who embraced everything it meant to be a Met, someone who really did give everything he had trying to give his best.

That burden of greatness isn’t a component of the athlete mythology. Unless they have a particularly tragic backstory, they’re simply expected to go about their business in the pre-defined social parameters. I ache in my soul for everything Harvey’s endured as an athlete.

He was living his dream.

Pitching for the Mets in the biggest media market in the country. One of the best at his position. Then, his body failed him. The lingering aches and pains. The mental anguish of not being able to perform to ability. All Harvey wanted to do was play baseball at a high level, to live that dream and everyone around him was eager to facilitate it.

It’s easy to understand how someone spirals into addiction in professional sports. The team wants the player to play and the player wants to be out there. First it’s a major injury and working their way back. Then it’s nagging pain. It all starts simple.

Professional athletes are not immune to the afflictions of normal society. They’re people too. But when they struggle with addiction, far too often sports media turns into TMZ. They’re bringing former teammates and coaches on to trade in conjecture and rumor.

All Harvey wanted to do was play baseball.

Now for the rest of his life, his struggles will always be right behind his accomplishments.

The memories

Throughout the afternoon, I’ve read too many bloody nose and coke jokes to count. Harvey who’s struggled with addiction for years because everyone around him was more interested in his talent than his person, reduced to a punchline from uncreative people too insensitive or ignorant to care.

That’s what’s so agonizing about Harvey’s retirement. At 34-years-old, Harvey isn’t a spring chicken, but that’s not ancient in baseball terms. It was never supposed to end like this for the Dark Knight of Queens. Anti-climactic, quietly with a heartfelt Instagram post thanking the fans for the memories.

The baseball community failed Harvey. Sports culture is pretty underdeveloped in terms of compassion and empathy. Your worth is tied to your ability to play. If the body fails, your utility is gone and you become an albatross. Institutions are a reflection of society and baseball shows just how far we have to go in understanding addiction.

The game of baseball is ill-equipped to handle such difficult situations. We revere athletes for their super-human abilities. Their ability to rise to the occasion at the most difficult of moment, to be a shining force in spite of what might be going on around them.

We never really know what anyone is going through unless they choose to let us in. For much of Harvey’s descent post 2015, it was “what’s wrong with him?” There was the very public breakup with Adriana Lima. There was a never ending stream of tabloid headlines treating Harvey’s struggles as a joke.

It’s morbid to think, but if someone like Harvey is struggling with access to all of those resources, what hope do the rest of us have?

That damn hope. It’s the eternal feeling I’ll tie to Harvey and his para-social role in my life. When the Mets were at their most listless, I knew that on Harvey day, I’d get to watch something truly special and it was entirely mine. No one could take that away from me.

Until baseball itself did.